It’s December again. That means elves on shelves are popping up in elementary classrooms (and living rooms) all over the place. The elf, children are told, keeps an eye on them and reports to Santa. The idea being that even when adults aren’t looking, someone still has their eyes on the children’s behavior.

It’s December again. That means elves on shelves are popping up in elementary classrooms (and living rooms) all over the place. The elf, children are told, keeps an eye on them and reports to Santa. The idea being that even when adults aren’t looking, someone still has their eyes on the children’s behavior.

The goal is simple, and it comes from a good place: teachers (and parents) know the holidays are approaching, children are getting excited, and adults worry (rightfully) that children will have extra difficulty regulating their behavior. So, the adults offer a reward. If you can stay in control and be good this month, even when you think no one is looking, the elf will tell the adults and you’ll be rewarded. Seems like a good idea, right?

The problem is that this kind of external motivation doesn’t help our children learn how to regulate their own behavior; it doesn’t help teach them to do the right thing. And worse, we’ve known about this … for a long time:

- In a 1993 Harvard Business Review article entitled Why Incentive Plans Cannot Work, Alfie Kohn noted “when it comes to producing lasting change in attitudes and behavior… rewards, like punishment, are strikingly ineffective. Once the rewards run out, people revert to their old behaviors.”

- In a 1999 meta-analysis of 128 studies, Deci, Koestner, and Ryan found that “as predicted, engagement-contingent, completion-contingent, and performance-contingent rewards significantly undermined free-choice intrinsic motivation [the ability to do the right thing simply because it’s the right thing] … as did all rewards, all tangible rewards, and all expected rewards.” They also noted that, “tangible rewards had a significant negative effect on intrinsic motivation … and this effect showed up with participants ranging from preschool to college.”

- In his 2009 book Drive, Daniel Pink discussed the seven deadly flaws of extrinsic motivation (what he calls carrots and sticks). These carrots and sticks can:

- extinguish intrinsic motivation

- diminish performance

- crush creativity

- crowd out good behavior

- encourage cheating, shortcuts, and unethical behavior

- become addictive

- foster short-term thinking

Admittedly, Deci, Koestner, and Ryan point out that “although rewards can control people’s behavior—indeed, that is presumably why they are so widely advocated—the primary negative effect of rewards is that they tend to forestall self-regulation. In other words, reward contingencies undermine people’s taking responsibility for motivating or regulating themselves” (my emphasis). But as teachers, isn’t one of our goals to teach our students to take responsibility and regulate their own behavior (not simply have us control it) – two things that our reward systems actually undermine?

Admittedly, Deci, Koestner, and Ryan point out that “although rewards can control people’s behavior—indeed, that is presumably why they are so widely advocated—the primary negative effect of rewards is that they tend to forestall self-regulation. In other words, reward contingencies undermine people’s taking responsibility for motivating or regulating themselves” (my emphasis). But as teachers, isn’t one of our goals to teach our students to take responsibility and regulate their own behavior (not simply have us control it) – two things that our reward systems actually undermine?

Are there a small percentage of students for whom simply getting through the holidays is the goal? Sure. But should this be the default goal for the entire classroom? Definitely not.

Teachers – we have to do more than just control behavior, we have to teach responsibility and self-regulation. We want to cultivate students who will do the right thing because it’s the right thing, not because we’ll reward them. The Responsive Classroom approach teaches us that effective reinforcing teacher language is, “clear and direct, genuine and respectful, and specific“; it’s not used in a manipulative way like reward systems. Teacher language is a powerful thing; tell your students they are working hard, and how their attention to behavior benefits others. “Verbal rewards – or what is usually labeled positive feedback in the motivation literature – had a significant positive effect on intrinsic motivation” (Deci, Koestner, and Ryan, 1999); this is what we really want. Aim to build a strong and trusting community in your classroom and you won’t need elves to extort good behavior out of your students (and they don’t really work anyway).

Of course, if you’re using an elf for non-coercive strategies like practicing writing letters to your elf or calculating the distance/rate of movement he had to get from one spot to another that’s totally fine. We just need to stop the bribery thing.

photo credit 1: Have I Got a Present for You! [Explored 12/2/2011] via photopin (license)

photo credit 2: Elf on the Shelf via photopin (license)

“Rewards do not create a lasting commitment. They merely, and temporarily, change what we do” Why Incentive Plans Cannot Work, Alfie Kohn. We professionals, have to do better than this (even in December).

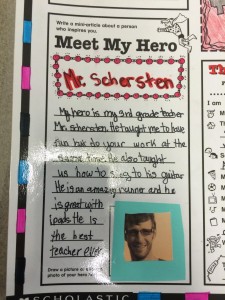

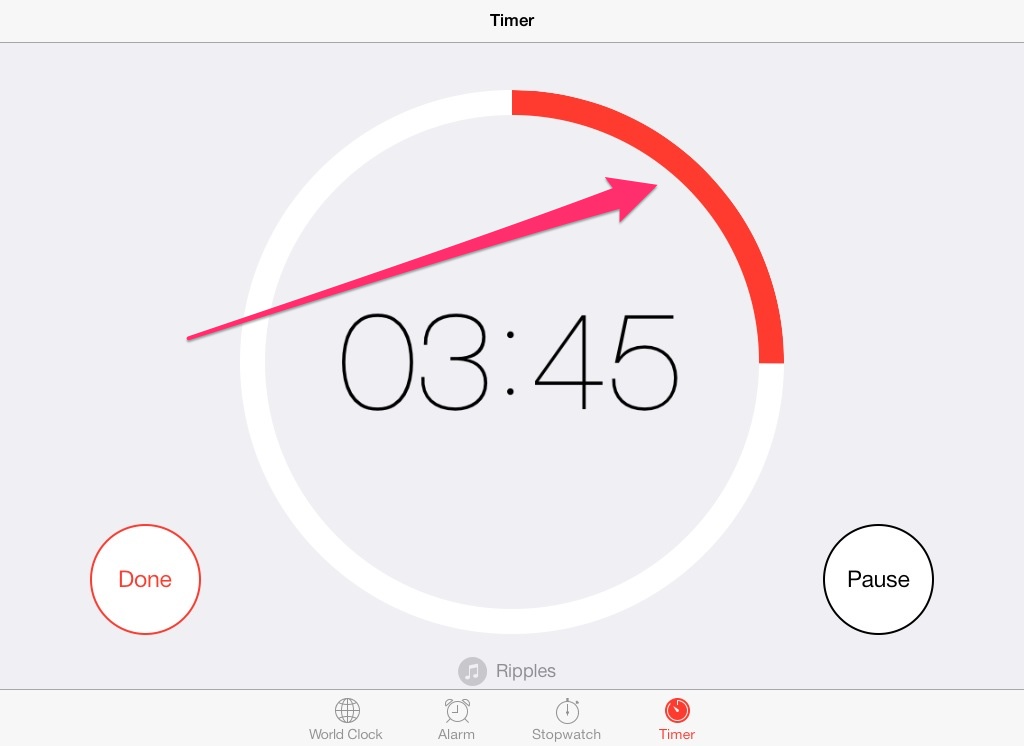

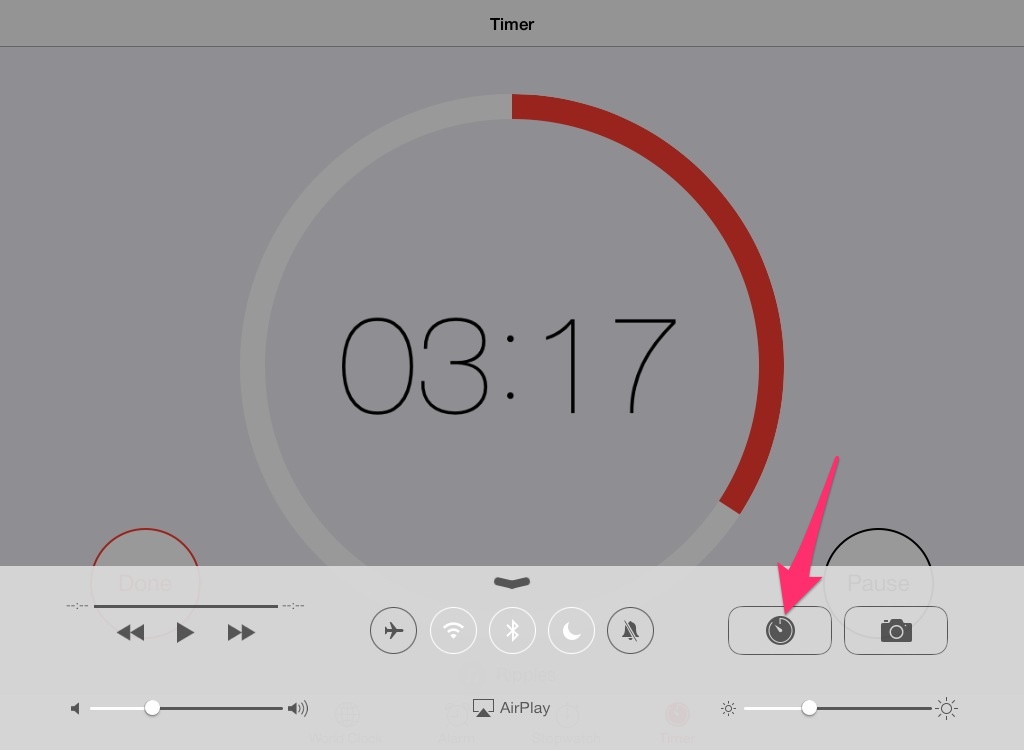

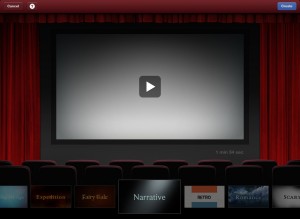

We started by talking about trailers and what they were for. All my students had seen them on TV and in the theaters. And a few even knew they were called trailers. From there we quickly previewed the trailer themes in iMovie. We then got the iPads out and kids got to spend more time looking at each trailer theme to choose the on that best fit them. I did have to spend some time explaining that the music and the text font were all they were going to keep; the content of the trailer would be completely rewritten by them.

We started by talking about trailers and what they were for. All my students had seen them on TV and in the theaters. And a few even knew they were called trailers. From there we quickly previewed the trailer themes in iMovie. We then got the iPads out and kids got to spend more time looking at each trailer theme to choose the on that best fit them. I did have to spend some time explaining that the music and the text font were all they were going to keep; the content of the trailer would be completely rewritten by them.