It’s The December Stretch at school, which for me means Parent Conferences. Five years ago I retooled my conferences and started requiring my students (5th and 3rd grade) to both attend and lead them. At our Back to School night, I took a moment to warn parents that this year’s conferences will be a little different.

Before making the shift I wrestled with the question of why do we have parent conferences, and if I bring kids will I ruin something? I came away thinking that we have parent conferences for a few reasons:

- We want to have face-to-face contact with the parents of our students.

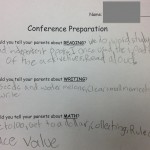

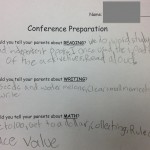

Individual student brainstorming.

- We want to give parents information about what their children are doing in school.

- We want to work with parents so we can support each other to ensure the success of students.

- We want a place to share possible concerns and strategize solutions to ensure student success.

Yea, I think having kids at the table for this will be just fine. Maybe even better.

Preparing for the Student-led Parent Conference

About a month before the conferences are scheduled the students start preparing:

- We brainstorm a list of all the things we’ve accomplished so far in school.

- Students begin to select some things they think are important enough that they might want to share them with their parents.

What can we bring to the conference?

- We look at what materials (such as work samples) the students might bring to the conference to help them show their parents what they are doing at school.

- I ask the students to select the 10-12 most important things they want to share with their parents, and what they will tell their parents about them. I require that they select at least one from each of the 5 core subject areas (reading, writing, math, science, social studies).

- Students set a goal to share with their parents about something they want to improve on this year. They also have to come up with an idea of how their parents and I can support them in that goal.

- We take some time to practice. Students pair up and give their presentation to a classmate. The goal is to have a presentation that lasts 10-11 minutes. Parents will ask questions which will make it a little longer.

The morning of the conference, I have a quick check-in with everyone presenting that day to make sure they’re all set.

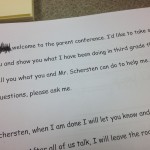

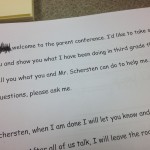

The Student-led Parent Conference

What we’re going to talk about.

The conference takes place around a table. Not a kidney or macaroni shaped table I can hide behind, but a round one. This is important; we all equal parties.

The student explains that he/she will share what they are doing and that I will not be participating until they are done sharing. The student then takes off. The parents ask clarifying questions as they go; the students field these questions. I make notes about anything I think the student may not have explained well so I can clear up any parent misconceptions when I join the conversation. The last thing the student shares is their goal.

When I join, I ask the student how they felt presenting in this format. The responses vary. I also ask (if their parents didn’t) what their favorite and least favorite subjects are, and why. In addition to forcing some more higher order thinking skills, this can be very useful information for me as I try to tailor my teaching to each year’s group.

With student and parents at the same table, some interesting conversations can happen. It’s great to tell everyone what going well, and talk about strengths. And if there are concerns, having students at the table is key for a couple reasons. First, everyone is on exactly the same page; we all get to be part of the same conversation. Second, if I want change the student has to be the one to make that choice; talking to parents isn’t enough.

For the last five minutes or so of the conference the student is asked to leave. I always openly joke that, “now we’re going to talk about you behind your back.” It’s clear from before we start that there will be time for me to chat with parents without students present.

But is 5 minutes enough? Yes, it is. It’s December; if I have something that takes more than a few minutes to talk about I should have already contacted the parents about it. Seldom does anything new come up here; more often we just reconnect on the things we taked about when the student was a part of the conversation.

The whole conference usually takes 25-30 minutes.

Final Thoughts

The parent response has been overwhelmingly positive. Parents think it’s great that their kids are preparing and giving an oral presentation. They see the value in the amount of responsibility I give students in selecting what they present. And they like the few minutes at the end without students, just in case they have something they want to discuss with me, sans kid. And since it’s built into the format, they don’t have to ask for that time.

Does it take time during the day to get ready? Absolutely. It usually ends up taking about 6 40-minute academic blocks. I steal time from across the academic areas. The students get a great experience presenting in front of a small audience. They get authentic experiences using higher order thinking skills as they organize the presentation, evaluate what they want to present, make the presentation, and answer questions on the fly. It’s always a joy to watch the conferences unfold.

Sure, it takes time to prepare the students, but it’s definitely worth it.

In January I read a blog post by Bill Powers about Daniel Pink‘s “Pronoun Test” from his book Drive. Basically, the Pronoun Test is about listening to employees talk about their organization and focusing on whether they refer to the organization as “we” or “they.” Mr. Powers wrote excitedly that his school was a “we” (our) school.

In January I read a blog post by Bill Powers about Daniel Pink‘s “Pronoun Test” from his book Drive. Basically, the Pronoun Test is about listening to employees talk about their organization and focusing on whether they refer to the organization as “we” or “they.” Mr. Powers wrote excitedly that his school was a “we” (our) school.